The Truth About Plastic Recycling: Unveiling eco packaging realities

eco-responsible tipsHave you ever wondered what happens to your plastic packaging after you dispose of it? The truth might surprise you.

The Dawn of Disposables: the Origins of Plastic

The journey of plastics began in 1869 with the invention of the first synthetic polymer, marking the birth of a new material that would shape the modern world. By 1907, the creation of Bakelite ushered in an era of synthetic possibilities. Plastics played a pivotal role during wartime in America, not only enabling the advent of television but also providing a glass alternative for aircraft windows with Plexiglas®. It was during this period that plastics found their way into novel applications, heralding a chemical revolution that promised to transform daily life.

— Source: Dow Chemical Company. “Styron! The Right Plastic!,” 1947. Advertisements from the Dow Chemical Historical Collection, Box 9. Science History Institute. Philadelphia.

The word plastic derives from the Greek πλαστικός (plastikos) meaning "capable of being shaped or molded," and in turn from πλαστός (plastos) meaning "molded."

Before World War II, there was a strong emphasis on the reusability of plastic containers and packaging across various industries. Yet, a paradigm shift was on the horizon. We had reached a point where plastics were no longer too valuable to discard. This shift was a green light for plastic packaging manufacturers to move away from promoting reusability, signalling the start of a disposable culture that would have lasting impacts on our environment.

Everyday items, once durable and reused, were swiftly replaced by disposable alternatives — from cups to silverware, disposability became the norm. It was during this era that our role as 'consumers' took hold.

Phillips Chemical Company advertisement printed in volume 54 of Modern Plastics. The advertisement promotes the chemical company's brandname plastic film, Marlex, a high density polyethylene plastic.

— Source: Charles H. Phillips Chemical Co. “Consumer Bag, Industrial Bag, Any Bag Is Our Bag. That's Marlex® in Action.” New York, New York: Breskin & Charleton Publication Corp., 1977. 103C004. Science History Institute. Philadelphia.

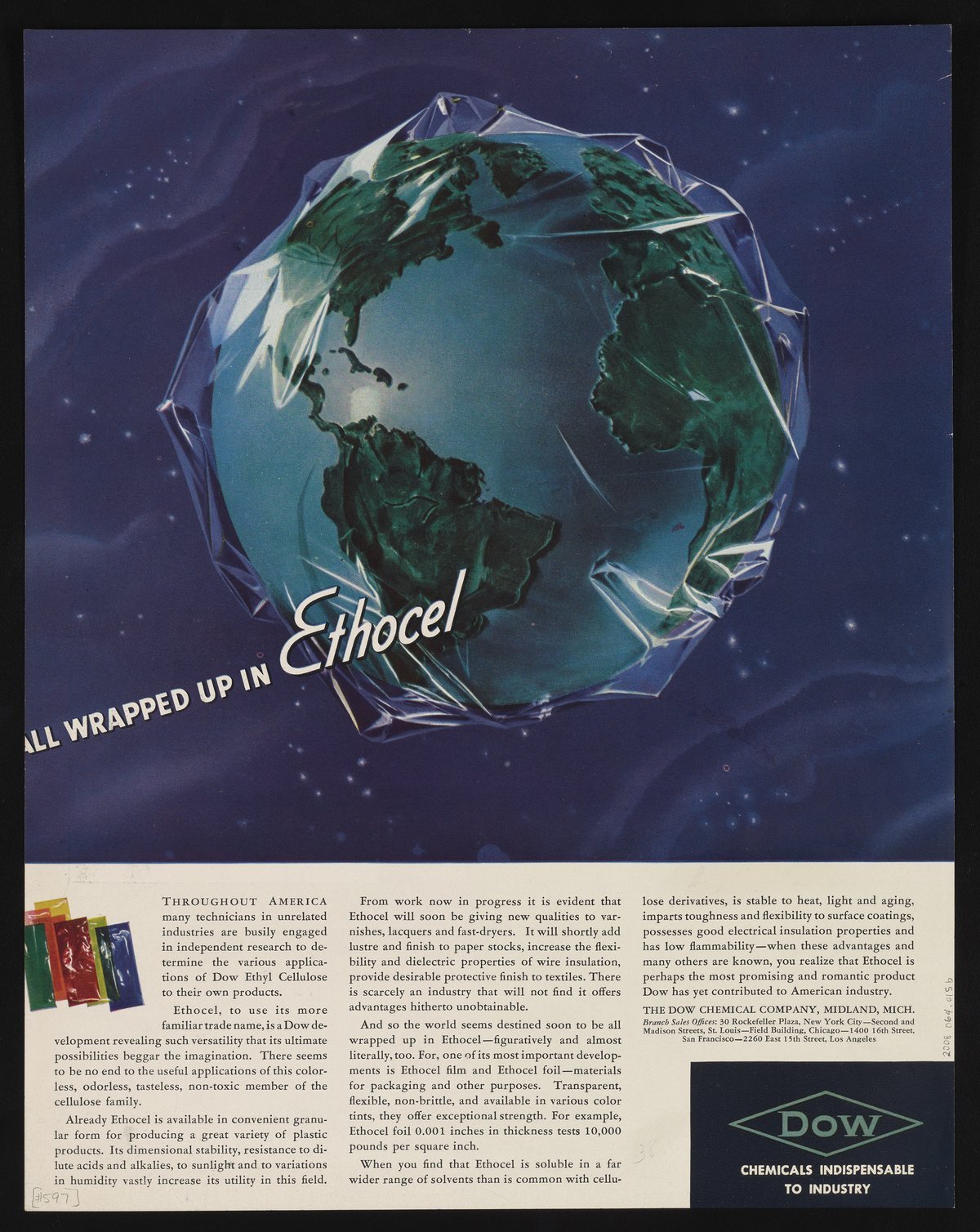

Advertisement for Ethocel, marketed for its flexibility and shock resistance under extreme high and low temperatures.

— Source: Dow Chemical Company. “All Wrapped Up in Ethocel,” 1938. Advertisements from the Dow Chemical Historical Collection, Box 9. Science History Institute. Philadelphia.

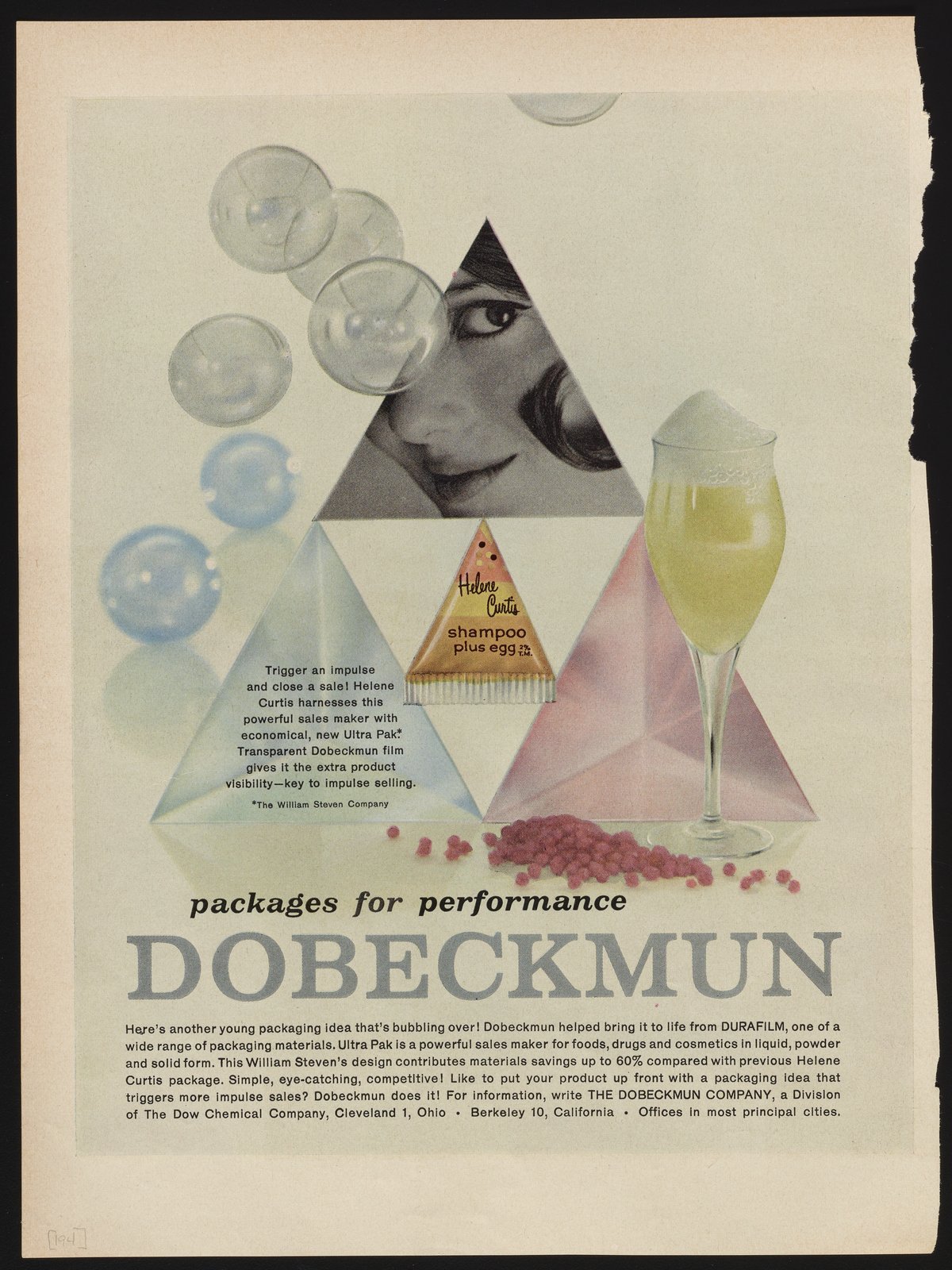

Advertisement for Durafilm, a transparent film. The advertisement details the use of Durafilm to create the new Ultra Pak for use packaging food, drugs, and cosmetics in liquid, powder, and solid form. Dobeckmun (short for Dolan, Becker and Munson, the company's the co-founders) was a leading manufacturer of cellophane bags and cigar pouches. The Dow Chemical Company acquired Dobeckmun in 1957.

The Recycling Myth Exposed

Did you know? Only a mere 9% of plastics make it through the recycling process.

According to this OECD report, only 9% of plastic waste is recycled globally, while 22% is mismanaged.

Dumpsite in South Tangerang, Banten, Indonesia — Source: Pexels

In the lush, creative expanse where design meets sustainability, we find ourselves at a crossroads, spurred by revelations that challenge our perceptions of plastic recycling. The "Fraud of Plastic Recycling" report, a rigorous examination by the Center for Climate Integrity, unfolds a narrative that is both alarming and enlightening. It exposes a stark reality: the vast majority of plastics, entrapped in a cycle of use and dispose, are never recycled. A mere 5-6% of plastics make it through the recycling process, with the rest destined for landfills, incineration, or, tragically, our natural environments.

Cover of the "Fraud of Plastic Recycling" report by the Center for Climate Integrity. This document explores the evidence that Big Oil and the plastics industry knew they were deceiving the public about plastic recycling, including never-before-seen documents published here for the first time.

Promises VS Reality

The report highlights how historical promises about plastic recycling have often fallen short. It’s a reminder of the value of transparency and the need for solutions that genuinely align with our environmental ethos.

This report pulls back the curtain on decades of deliberate misinformation by the petrochemical industry, revealing a concerted effort to sell the public and policymakers on the viability of plastic recycling. It's a story of ambition, where the pursuit of profit overshadowed the pressing need for genuine sustainability. Companies like ExxonMobil, as the world’s top producer of single-use plastic polymers, have played pivotal roles in crafting this deceptive narrative, promoting recycling as a panacea while knowing its feasibility was a far cry from their claims.

The Society of the Plastics Industry encouraged consumers to dispose of plastic dry-cleaning bags. SPI, 1959.

An SPI pamphlet from 1959 explained that customers should “never keep a plastic bag after it has served its intended usefulness. Destroy it: Tear it up … or tie it in a knot … and throw it away.” To do otherwise “is the worst mistake a mother could make.”

The Paradox of Plastic Pollution

"Between 1950 and 2015, over 90% of plastics were landfilled, incinerated, or leaked into the environment, underscoring the stark reality that the vast majority of plastic waste is not, and has never been, recycled."

The narrative of plastic recycling is fraught with ironies, one of which is sharply underscored by the formation of the Council for Solid Waste Solutions in 1988. Major plastics producers, including industry giants like Exxon Chemical, came together under the Society of the Plastics Industry (SPI) to ostensibly tackle the environmental issues posed by plastics across the US. Yet, there's an inherent contradiction in the polluters taking charge of the promise to offer long-term solutions to the very problems they help perpetuate.

The Council's mission was ambitious, aiming to address the nation's solid waste problems with strategies like developing recycling technology and promoting waste-to-energy incineration. With a considerable budget, one would expect significant strides in mitigating the impact of plastic waste. However, the unfolding reality, as detailed in the report, paints a different picture — one where the promise of a plastic recycling revolution remains largely unfulfilled.

Landfill near Pattaya City, จ.ชลบุรี, Thailand — Source: Pexels

"In 1994, recognizing that plastic could not be adequately recycled through mechanical recycling, SPI made a bid to the Attorney General of Oregon asking that plastic waste processed into fuel at an in-state pyrolysis facility be recognized as 'recycled' so it could meet its 25% recycling target." This is just one of the examples of how the industry has historically attempted to classify less sustainable practices as recycling to meet regulatory targets. Sad.

The recycling symbol

The Society of the Plastics Industry cleverly co-opted the recycling symbol — a trio of arrows that the environmental community recognizes — by placing numbers from 1 to 7 in the middle. These numbers correspond to different types of plastics. They pitched this emblem to state governments as a "classification system," promoting it as an alternative to enacting plastic bans, bottle deposit requirements, or compulsory recycling laws.

This strategy was deployed even though economically viable recycling methods for these plastics weren't available.

As a result, a widespread misconception has taken root among many Americans: the belief that any plastic adorned with this emblem is recyclable.

Polluters knew decades ago that plastic recycling was “virtually hopeless.”

Despite our best intentions, a staggering amount of plastic doesn't make it back into the recycling loop. It’s a wake-up call to reconsider our packaging choices and their lifecycle. Recycling plastic is tricky, and the economics of chemical recycling processes play a big role.

“Separation of plastics from municipal solid waste is neither technically nor economically feasible at the present time and probably will not be in the future.”

A 1973 study concluded that plastic waste is not suitable for pyrolysis (what industry today often calls Advanced Recycling), a process that shared many of the same obstacles as mechanical recycling. Arthur D. Little, 1973

— Source: Fraud of Plastic Recycling report by the Center for Climate Integrity, p.28

The executive board members of the Council for Solid Waste Solutions, including many of the world’s largest fossil fuel and petrochemical companies, were listed on the cover of the organization’s industry newsletter, Handlers News. CSWS, 1991

— Source: Fraud of Plastic Recycling report by the Center for Climate Integrity, p.15

Why is plastic challenging to recycle?

Understanding the intricate challenges of plastic recycling is crucial. The "Fraud of Plastic Recycling" report illuminates these complexities, revealing why a shift towards more sustainable practices is not just beneficial but essential.

Sorting and Recycling Technologies: One of the primary hurdles in recycling plastics is the sorting process. Plastics need to be meticulously sorted by type and color to ensure they can be recycled properly. Advanced sorting technologies exist, but their adoption is inconsistent and often cost-prohibitive, limiting their effectiveness on a global scale.

Quality Degradation: Each time plastic is recycled, its quality diminishes. This phenomenon, known as 'downcycling,' results in recycled plastics that are weaker and less versatile than their virgin counterparts.

Economic Viability: The economic model underpinning plastic recycling is fraught with challenges. The cost of collecting, sorting, and processing plastics often outweighs the value of the recycled material produced. This economic imbalance poses a significant barrier to the expansion of recycling programs, akin to the high costs associated with sourcing rare, sustainable ingredients for wellness products — a worthy investment that demands both commitment and creativity to navigate.

Limited Recycling Infrastructure: Many regions lack the necessary infrastructure to manage plastic waste effectively. This shortfall means that even when consumers and businesses do their part, the systems required to process this waste are overwhelmed or non-existent.

Chemical Recycling — A Promise Unfulfilled: The report also casts a critical eye on chemical recycling, a technology touted as a game-changer for plastic waste. Yet, the reality is that these technologies are still in their infancy, with operational and financial hurdles that significantly limit their scalability and impact. It's a reminder that innovation, while essential, must be grounded in practicality and effectiveness to truly advance our sustainability goals.

— Source: Fraud of Plastic Recycling report by the Center for Climate Integrity, p.6

“The majority of plastics cannot be recycled - they never have and never will be”

“Plastics are part of a sector known as “petrochemicals,” or products made from fossil fuels such as oil and gas. More than 99% of plastics are produced from fossil fuels. There are “thousands of different types of plastic, each with its own chemical composition and characteristics.” The vast majority of these plastics cannot be “recycled”—meaning they cannot be collected, processed, and remanufactured into new products. To date, viable markets only exist for polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and high-density polyethylene (HDPE) plastic bottles and jugs. These are known as plastics #1 and #2, respectively, under the industry’s Resin Identification Codes (RICs).

After conducting a 10-year review on plastic recycling, in 1991, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) concluded that “it appears that at the present only two types could be considered for making into high quality objects, PET and HDPE,” specifically those sourced from bottles. This remains true more than 30 years later. While a minority of municipal recycling programs across the country may collect plastics with RICs #3-7, they do not actually recycle them. Instead, such plastics are incinerated or sent to landfills.”

— Source: Fraud of Plastic Recycling report by the Center for Climate Integrity, p.6

Misleading Public Campaigns

The plastics industry embarked on a decades-long campaign, misleading the public and policymakers about the feasibility of plastic recycling. Despite clear evidence to the contrary, they promoted recycling as a viable solution to the plastic waste crisis, and we believed them.

— Source: Fraud of Plastic Recycling report by the Center for Climate Integrity

— Source: Fraud of Plastic Recycling report by the Center for Climate Integrity

— Source: Fraud of Plastic Recycling report by the Center for Climate Integrity

Moreover, the deceptive practices of greenwashing extend beyond mere recycling symbols and into the very heart of our consumer culture, where even today, brands such as those led by prominent figures or household names in the beauty industry contribute to the confusion. They craft an image of environmental friendliness while their actions continue to burden our planet with waste.

For more insights on creating an ethical business and why that matters, check out our article here.

“Recycling cannot go on indefinitely, and does not solve solid waste problem.”

— Quote Source: The executive director of the Vinyl Institute (a spinoff organization of SPI) shared “key considerations to be made when considering recycling” with other members of the plastics industry. Gottesman, 1989 - Fraud of Plastic Recycling report by the Center for Climate Integrity, p.9

At the heart of this statement lies the truth about the recycling process itself — it is not an infinite loop. Each time plastic is recycled, it undergoes physical and chemical changes that degrade its quality and value. This degradation means that plastics can only be recycled a finite number of times before they become too weak or contaminated to be useful.

— Source: A draft “Solid Waste Fact Sheet,” created by the Vinyl Institute, was stark in its assessment of the viability of recycling to address plastic waste issues. VI, 1986

Fraud of Plastic Recycling report by the Center for Climate Integrity, p.10

Municipal solid waste (MSW), commonly known as trash or garbage in the United States and rubbish in Britain, is a waste type consisting of everyday items that are discarded by the public.

The emphasis shifts from relying solely on recyclable materials to exploring other avenues of sustainability, such as reducing overall material use, designing for longevity, and adopting circular economy principles where waste is designed out of the system.

A New Path Forward

The findings illuminate the need for a paradigm shift – from a linear economy, where disposability reigns supreme, to a circular one, where every material is valued and nothing is wasted. This transition is fundamental, not just in how we design and produce but also in how we perceive our role in the larger environmental narrative.

Innovation in sustainable materials is at the heart of our mission. We are inspired by the challenge to design packaging solutions that are not only beautiful but also beneficial to our planet. From bioplastics to compostable materials, our journey is about exploring and embracing alternatives that reduce our ecological footprint.

One of our favourite clients, RUA Beauty, embraced our sustainable packaging solutions, significantly reducing their environmental footprint. Here's how we did it. We introduced a new refill system to tackle the plastic soup problem: we introduced a refill system to minimize waste and selected materials that echoed RUA's commitment to the planet. The infinitely recyclable glass bottles, topped with aluminium caps, not only reduce plastic use but also add an elegant touch to the brand's aesthetic. By reusing the same dropper pipettes, we significantly cut down on plastic waste, aligning perfectly with the brand's mission to keep our oceans clean.

RUA Nordic Beauty - Remove Multi-Use-Cleanser | View the full project here

The impact was immediate. Not only did RUA see a reduction in their carbon footprint, but their commitment to sustainability also resonated deeply with their customers, fostering a stronger brand connection. This shift towards eco-friendly packaging has set a new standard in the beauty industry, proving that luxury and sustainability can go hand in hand.

For more inspo, explore our portfolio of eco-friendly packaging designs here.

Beyond Recycling: Embracing a Holistic Approach

Acknowledging the limitations of recycling inspires us to broaden our vision of sustainability. It involves:

Reducing: Minimizing the amount of packaging used and opting for designs that require less material without compromising the integrity and appeal of products.

Composting: For the wellness and beauty industry, leaning into fully compostable packaging materials for products that align with this end-of-life option can significantly reduce the solid waste footprint.

Reusing: Encouraging the use of refillable and reusable packaging options that extend the lifecycle of containers far beyond that of single-use packaging. For example, The Cradle to Cradle (C2C) design philosophy reshapes how we think about sustainability. It's a blueprint for products designed to be used, reused, and repurposed, never ending up as waste. This innovative approach ensures materials circulate in an infinite loop, supporting both the planet and the economy. It's sustainability, but smarter.

“From formulation within our supply chain to packaging and social impact, Cradle to Cradle Certified® provides us with a credible, independent improvement framework to confirm that our sustainable approach is the right one. Having this good design in place ensures good business can happen.” - Jo-Anne Chidley | Founder & CEO

— Photo: Courtesy of BeautyKitchen

Empowering Change Through Design

The "Fraud of Plastic Recycling" report is a call to action, urging us to confront the realities of plastic waste and to advocate for transparency, accountability, and genuine solutions. It's a reminder that as designers, brands, and consumers, we hold the power to demand change and to support practices that prioritize the health of our planet. The insights from this report not only reinforce our commitment but also urge us to delve deeper into the alternatives that truly embody the essence of recyclability and environmental stewardship.

LIV Botanics educates their customers: their primary packaging is made with elephant grass fibres grown close to the production site and is totally glueless and realistically recyclable.

— View the full project here - Designed by Giada Tamborrino Studio

At GT Studio, we are more committed than ever to pushing the boundaries of sustainable design. We believe in the power of creativity to spark change and in the resilience of our community to embrace a more sustainable future. Together, we can redefine the narrative around recycling and sustainability, turning insights into action for a greener tomorrow. By embracing this challenge, conscious brands can forge a path where the focus shifts from managing waste to preventing it in the first place.

Let's embark on this journey together, transforming challenges into opportunities for innovation, and paving the way for a future where design and sustainability are inextricably linked. Discover how our ethical packaging design services can help your brand stand out and positively impact the environment.

We'd love to hear your thoughts on sustainable packaging solutions. Have you encountered any innovative practices? Share your stories in the comments below!

Sources:Fraud of Plastic Recycling Report by the Center for Climate Integrity

Historical Posters on Plastics by Science History Institute Museum & Library Digital Collection

History of Plastics - Retrieved from Wikipedia and Science Museum

Inspired by the journey towards sustainable packaging? Share this article with your network and join the conversation on eco-friendly design. Let's make sustainability the core of every business’ branding together.

Share on

Related articles